-

This image of Robert Graves comes from WarPoets.org. In his account of World War I, Robert Graves noted a staggering fact which, if it’s known at all, is too often forgotten and yet never should be: “At least one in three of my generation at school was killed [in World War I], and the average life of the infantry subaltern on the Western front was, at some stages of the war, only about three months.” I quote here Robert Graves’s account of the first World War because it’s vital in understanding his poem below.

DEAD COW FARM

An ancient saga tells us how

In the beginning the First Cow

(For nothing living yet had birth

But Elemental Cow on earth)

Began to lick cold stones and mud:

Under her warm tongue flesh and blood

Blossomed, a miracle to believe:

And so was Adam born, and Eve.

Here now is chaos once again,

Primeval mud, cold stones and rain.

Here flesh decays and blood drips red,

And the Cow’s dead, the old Cow’s dead.— Robert Graves (1895–1985)

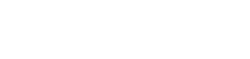

The following is a draft which Robert Graves corrected in the final manuscript. I include it here primarily as a point of interest. Note the self-editorial acumen in how Robert Graves changed the opening of his war poem (“I’ve read an ancient saga, how” becomes “An ancient saga tells us how”):

Image from World War I First Digital Archive

Note the self-editorial acumen, as I say above and repeat again now, in how Robert Graves changed the opening of his war poem — and the reason I repeat myself here is to emphasize that this is a war poem and cannot be properly understood outside the context of war. It simply cannot.

War is chaos.

World Wars are the most chaotic wars of all.

Retrospectively, when we have decades of history and the wisdom of history to draw from and when we therefore know the outcome of wars — World War I, for example, wherein Captain Robert von Ranke Graves was brutally injured and pronounced dead (forever after shell-shocked from this experience) — it becomes almost preposterously simple to let slip the chaos created by war. By this I mean that it becomes almost preposterously simple for us to lose perspective on the full context of war because that context fades rapidly from memory after the immediacy of the horror has passed.

It then becomes tragically simple to forget that when you’re living through the atrocities of wartime — as we are now living through precisely such atrocities, in a bioterror war conducted with unprecedented stealth — the final outcome is always uncertain.

Will the malevolent chaotic forces responsible for the initiation of aggression prevail?

Will the people being attacked by these forces of aggression, the individual humans striving to battle back, lose their lives?

I say to you again: it becomes preposterously, tragically simple to forget the chaos created by war — the utter and yet unutterable chaos that war generates.

Make no mistake, however, and please never forget: all war is chaos, and the outcomes are always far from certain.

Never forget also: the root of all war is found precisely in the initiation of force and aggression. It is found precisely here and nowhere else.

War is the instigation of force and aggression.

War is the instigation of force and aggression.

War is chaos.

Chaos is the opposite of life.

War is by definition chaos, and it can only be instigated by governments, because government is the only institution that possesses legal control over — and legal privilege to use — force and coercion, and to instigate force and coercion.

Government alone is responsible for all wars in history, all wars presently, and all wars in the future, because war is the instigation of force politically enacted and state-sanctioned.

The psychological manipulation and confusion and terror that issue from the well of chaos are exactly what the political purveyors of force and the state ministers of coercion seek first and most fundamentally of all to instill within humankind — to instill and sustain: chaos and the terror and confusion that chaos generates.

The first two lines of Robert Graves’s poem deliberately (yet obliquely) echo the Book of Genesis — specifically, I believe, in how the beginning of time is biblically portrayed, which is then reinforced in line eight, when Robert Graves names Adam and Eve explicitly.

“An ancient saga” — also from the opening — refers to certain obscure Nordic mythologies concerning a mythical cow and the creation of life on earth.

The Cow in this poem is a figurehead and symbol of ultimate good.

The Cow is a life-giving force standing diametrically opposed to the forces of chaos.

Chaos is death.

It’s neither poetic accident nor linguistic coincidence that “Cow” and “God” both contain three letters.

The Cow is thus capitalized in the poem to symbolize God.

I find in this fact the key to unlocking the entirety of Robert Graves’s brief, bleak, beautiful, cryptic poem and the fundamental meaning Graves intended, which meaning is profound. Robert Graves, in all his poetic imagination and syncretic brilliance, has integrated two disparate origin-myths and made them into one.

Robert Graves, like all other war poets, was one soldier striving to speak for himself and for the countless million non-writing soldiers: striving to articulate poetically the monstrous chaos created by war, including most terrifying of all the unknown outcomes of these acts of aggression and the initiation of force, which is war, which is chaos, which is death.

Will these forces of death prevail?

The answer to that question is entirely unknown ahead of time.

As the later poet Edna St. Vincent Millay memorably wrote, though in a completely different context:

The smell of the earth is good.

It is apparent there is no death.

But what does that signify?I have an answer to her question:

There is nothing greater than life.

The will is eternal.

Goodness is timeless.

Dead Cow Farm — Robert Graves